From 18th to 19th century

The manufacture of the first horns, at the end of the 17th century, was carried out by the boilermakers who also produced trumpets, timpani and cymbals, alongside common copper utensils. Among the oldest “makers” or “makers” of horns, we note the names of Crétien (or Crestien, or Chrétien), of Le Brun and especially of Raoux, four generations of which followed until the 19th century.

Etienne-François Périnet

It was with the latter, Auguste Raoux, that a young worker from Savoy learned the trade in the 1820s. Etienne-François Périnet – that’s him – learned quickly: he did not only have manual skills. , he also has an insatiable curiosity and a constantly keen sense of observation. At Raoux, we make everything, but he is particularly interested in piston instruments recently appeared in Germany and which are still in their infancy. In 1829, François Périnet (who gave up his first name) had the idea of adding a third piston to the cornet which until then had only two, thus giving the instrument a full scale of notes. And to better exploit this innovation, he decides to set up on his own.

From now on, inventions will follow one another. In 1834, it is a new model of cone which is none other than the one we know today. In 1838, he developed a piston with staggered openings, much more efficient than the process then in use: known under the name of “Périnet system”, it is still used today for the trumpet and for certain horn models. The year 1841 saw the creation of a “piston-bass”, a large four-piston instrument which prefigures the modern tuba …

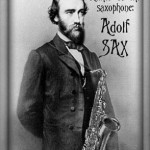

Adolphe Sax

But Périnet has a formidable competitor in the person of Adolphe Sax, an instrument maker of Belgian origin, inventor among others of the saxophone and of the saxhorn family (alto, bass, tuba, etc.). Sax is not only an imaginative creator, he is also a wise and solid financier, coupled with a shrewd schemer. In 1845, he managed to obtain total exclusivity for the supply of wind instruments to the armies and the navy as well as to public theaters. The market is huge, and above all Sax’s instruments thus benefit from official recognition which marginalizes others.

The blow is hard for Périnet. With his former employer Raoux and three other instrument makers, he formed a committee to denounce this abuse. But the letter they send to the Minister of War remains ineffective. For his part, Auguste Raoux engages in long and ruinous procedures against Sax, procedures which will not succeed and will force him to sell his business in 1857. François Périnet, for his part, adopts a wiser course.

Of course he can compete with Sax on a technical level, but he does not have the “financial surface” or the network of influences that would allow him to stand up. So, turning his back on piston instruments to which he nevertheless made notable improvements, he now devotes himself exclusively to the hunting horn, an area where there is little chance that Sax will give him offense. And just as he has always strived to be at the cutting edge of technology, as his successive inventions have shown, he also intends to be the best there too.

The first horn companies

No doubt he foresaw the profound mutation that the horn began at the end of the 1840s. Since the beginning, only one or two horns are sounded and the instrument itself is not designed to have a large power of sound. But with the bass part that appeared in 1848, it became possible to form trios or larger groups. It was the time when the first horn societies were formed and when we started to sound in groups. It is, moreover, very much in the spirit of the times. The romantic wave that has invaded all areas for two decades has introduced a certain taste for excess: in music, the fashion is for powerful sound effects (and even “noisy” according to the critics of the time). Anything that can help is obviously very much appreciated, and the horn is no exception.

The merit of François Périnet is to understand this evolution even though it is in its infancy, and to support it by innovating once again in terms of instrument making. His research on the cornet or the bass – among others – familiarized him with all the technical aspects of the trade. He knows how to work on ease of emission, accuracy, timbre or power, to achieve an instrument as perfect as possible. The lack of sound, precisely, seemed to him to be the weak point of the trunk as it existed at the time. Just imagine a group that would have more powerful instruments …

He is well aware that the solution lies essentially in the shape of the pavilion. That of the existing proboscis, which has hardly undergone any change since the origin, has a rather flattened edge with a narrow thunder which suddenly flares out. The sound, rather soft, can be brilliant in the forté but lacks a little fullness.

A powerful sound

To give it, you obviously have to broaden the thunder which modifies the general sound balance and requires readjusting all the other manufacturing data. It is patient, long-term work. It took François Périnet several years – until 1855 – to develop a horn profile offering powerful sound and quality of tone without harming the other characteristics of the instrument. But it is a total success, to the point that this new model is quickly copied and generalized, replacing everything that existed until then. It remains today the standard of the trunk.

However, if Périnet patented his first inventions, he did not see fit to do so for what was in his eyes only a simple improvement. So he now has to struggle to hold his place, and the best way is to find a partner to develop the business. It was done in 1859, the sign becoming “François Périnet, Pettex-Muffat & amp; Cie”, and the workshop leaving Paris for larger premises in Passy. The following year, Pettex-Muffat launched its famous relief garland horn designed by Garnier.

In all likelihood, François Périnet died in 1862 or 1863. His successors would bring manufacturing back to Paris, but faithfully uphold the tradition of quality that he had established, taking care to keep the brand in his name as a guarantee of excellence. Even today, isn’t it enough to hear “Périnet” being said for one to immediately think “is wrong”?

Is there a Perinet secret?

The manufacturing processes are for the most part known, and modern achievements have in many cases proved their worth. The know-how that makes the difference – lies largely in the design and assembly, because a quality instrumental invoice cannot do without an artisanal environment. The current Périnet range thus maintains a subtle balance between a solid practical experience, essential, and a sure mastery of the most recent technologies, which is also decisive. If there is a secret, it is above all to be found in this relentlessness to always do better which has been the hallmark of the brand from the start. Each Périnet trompe is unique: this is why each one now wears a number that personalizes it.

Yannick Bureau is the successor of Maison Périnet

Since 1994, after his uncle Michel BUREAU, he has been in charge of both design and production monitoring. He created and runs with an educational team, the Périnet academy at the House of Hunting and Nature in Paris where he has implemented the best techniques for learning the instrument, which allows him to advise bell ringers and huntsmen on the choice of an instrument and mouthpiece.

History of Maison Périnet

For the amateur of old horns, the table below retraces the successive stages of the mark and makes it possible to date a period instrument according to the address which it carries.

Paris

François Périnet – 1829-1838

42, rue Bourbon Villeneuve - Paris

François Périnet – 1838-1849

23, rue des Bassins - Passy

François Périnet – 1849-1858

23, rue des Bassins - Passy

François Périnet, Pettex-Muffat & Cie – 1859-1862

rue des Bassins, 23 - Passy

François Périnet, Pettex-Muffat & Jolly Pottuz succr. – 1863-1864

23, rue Copernic - Paris

François Périnet, Pettex-Muffat & Jolly Pottuz succr. – 1865-1869

37, rue Copernic - Paris

François Périnet, Pettex-Muffat & Jolly Pottuz succr. – 1870-1871

37, rue Copernic, près de l‘arc de l’étoile - Paris

François Périnet, Pettex-Muffat & Jolly Pottuz succr. – 1871-1874

27, rue Copernic, près de l‘arc de l’étoile - Paris

François Périnet, Pettex-Muffat & Jolly Pottuz succr. – 1874-1882

31, rue Copernic, près de l‘arc de l’étoile - Paris

François Périnet, Pettex-Muffat & Jolly Pottuz succr. – 1883-1895

31 rue Copernic, près l‘arc de l’étoile - Paris

François Périnet, Henri Pettex-Muffat succr. – 1900-1904

40 bis, rue Fabert - Paris

François Périnet, Emile Dhabit succr. – 1905-1923

40 bis, rue Fabert - Paris

François Périnet, Maurice Valéry succr. – 1921-1939

40 bis, rue Fabert - Paris

François Périnet, Tutin & Cheval succr. – 1940-1944

40 ter, rue Fabert - Paris

François Périnet, Cheval succr. – 1945-1967

Périnet - Paris

François Périnet, Michel Bureau succr. – 1967-1994

Viaduc des Arts - Paris

François Périnet, Bureau succr. – 1994-1999

Paris

Périnet, Bureau succr. – 2000